Three hundred thirty one million, four hundred forty nine thousand, two hundred and eighty one. According to the US Census Bureau, that is total residential population of the United States as of April 1, 2020. That number is a form of data theater.

Statistics, in their original form, is the state’s science. State-istics. The original name, btw, was political arithmetic. Today, we distinguish the state’s statistics by calling them official. These are data in the oldest of senses. The Latin root of data comes from a notion of “the givens.” The state is producing statistics that are then given to the public as data. And those givens are then treated as facts.

Links

![[REPOST] – The 27th edition of the European Security Course is underway! [REPOST] – The 27th edition of the European Security Course is underway!](https://christianbuehlmann.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Fn5S4mgXwAAsBFJ-900x450.jpg)

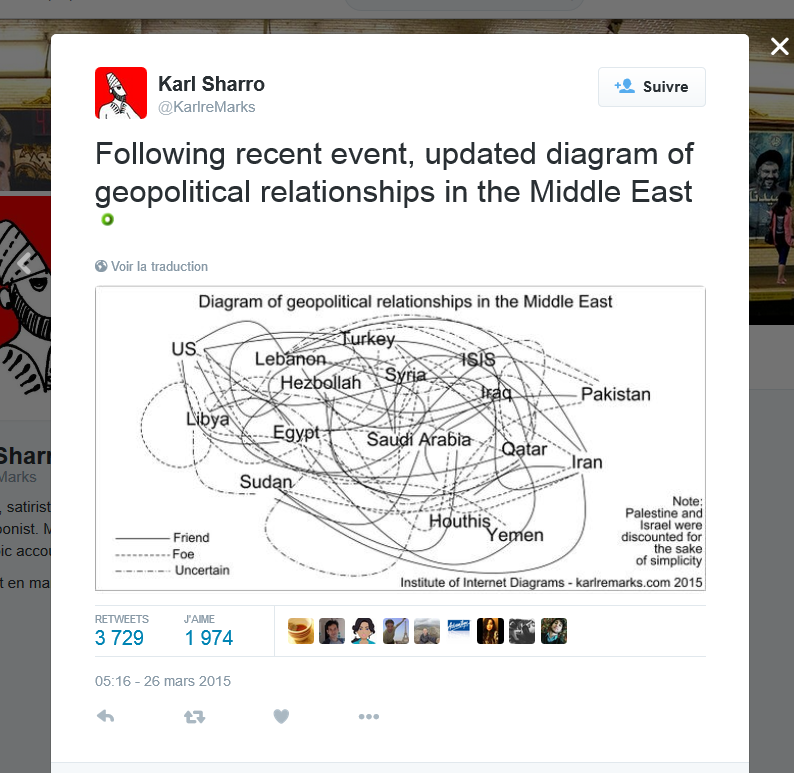

![[RAMAGE: Zenpundit.com] Karl Sharro’s two modes of “simply” explaining the Middle East [RAMAGE: Zenpundit.com] Karl Sharro’s two modes of “simply” explaining the Middle East](https://christianbuehlmann.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/bf57a306d73d535c8ca073929ee09010-1a0.jpg)